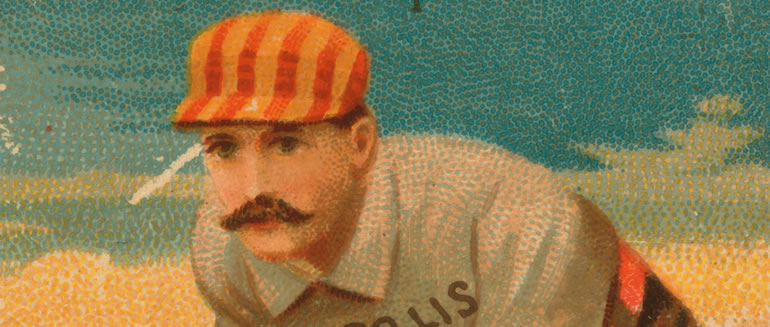

The Hall of Fame Case for Jack Glasscock

Jan 18, 2013 by Adam Darowski

There are so many ways to enjoy baseball. From an early age, I was enthralled by the history of the game. In the last few years, I’ve become deeply interested in the statistical and analytical side of the game. My interest in both led to the creation of the Hall of Stats.

Naturally I became very interested in the players in the Hall of Stats who are not in the Hall of Fame. The list is dominated by modern players for a couple reasons. First, it’s getting harder to get into the Hall of Fame because of the anti-recency bias. Second, modern players simply haven’t had as many chances to get in through the BBWAA and the various Veterans/Era committees. For those reasons, there were only four players who started their careers before 1955 who comfortably cleared the Hall of Fame borderline. One was Shoeless Joe Jackson (who, of course, is banned). The other three—Deacon White, Bill Dahlen, and Jack Glasscock—played in the 19th century.

In early 2013, I joined SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legends committee. In the fall of 2013, I became the Chair of the committee. As a result, my focus on these overlooked 19th century stars has gone from an interest to a passion.

White, the Overlooked Legend selection in 2010, was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2013. Dahlen, our 2012 Overlooked Legend, came just two votes shy in 2013 and then four votes shy when the Pre-Integration Era Committee met again for the 2016 election. The third, Glasscock, is the most overlooked of them all. He is actually so overlooked that he was not named an Overlooked Legend until 2016 (the eighth year the honor was given). Glasscock didn’t even appear on the Hall of Fame’s Pre-Integration Era ballot in 2013 or 2016.

What makes Jack Glasscock so Hall-worthy?

Hall Rating

The Hall of Stats is powered by a formula called Hall Rating. Hall Rating combines Baseball-Reference’s Wins Above Replacement (WAR) and Wins Above Average (WAA) into a single number that represents how good—strictly according to these value-based statistics—that player’s Hall of Fame case is. There are 215 players in the Hall of Fame. The 215th-best eligible player by Hall Rating is given a Hall Rating of 100. This illustrates where the Hall of Fame borderline would be if the Hall was populated simply by this metric. Everyone with a Hall Rating above 100 is in the Hall of Stats. Everyone below 100 is out.

Glasscock’s Hall Rating of 129 ranks him 101st all time among eligible players. In other words, he’s not just a borderline Hall of Famer. If the Hall was split in half, he’d fit perfectly into the top half. His induction (like many of the players toiling on the current BBWAA ballot) would improve the overall quality of the Hall of Fame. His Hall Rating is similar to BBWAA selections like Ryne Sandberg (128), Ernie Banks (127), Tony Gwynn (126), and Willie McCovey (125).

Glasscock, called “King of the Shortstops” in his day, ranks 14th all-time among shortstops in Hall Rating. He ranks ahead of eleven current Hall of Fame shortstops.

Let’s see how that’s possible.

WAR and WAA (and My Adjusted Versions)

Glasscock’s raw WAR total of 61.9 ranks 16th all-time among eligible shortstops. That puts him ahead of eight Hall of Famers, from Luis Aparicio down to Phil Rizzuto. By WAA he looks even better, ranking 14th (ahead of ten Hall of Famers). For Hall Rating, I use an adjusted version of WAA that eliminates negative seasons (and makes some other adjustments that Glasscock doesn’t take advantage of). Glasscock remains 14th in adjWAA.

My adjustments to WAR do help Glasscock, though. Glasscock played at a time when the schedules were shorter, hurting his ability to compile the same WAR totals players do today. My adjusted version of WAR accounts for this (splitting the difference between Glasscock’s team’s schedules and a 162-game schedule). Glasscock moves up seven slots to 10th in adjWAR (ahead of 13 Hall of Famers).

It’s worth noting here that I feel the shortstop position is among the strongest in the Hall. The lowest ranking shorstops are Phil Rizzuto and Rabbit Maranville. Both were inducted for good reasons, though their cases are still flawed (particularly statistically). Still, it’s not like we’re comparing Glasscock to Tommy McCarthy-type mistakes. These are almost all legitimate Hall of Famers.

It’s also worth noting that these rankings include Glasscock’s total contributions—not only at the plate, on the bases, and in the field, but also on the mound. He didn’t pitch much, but he did throw seven innings and it hurt his overall numbers slightly. If I only included his contributions as a position player, he’d look a bit better.

WAR Components

Next, let’s look at the components of WAR, particularly batting and defense. Glasscock was a solid hitter, batting .290 for his career (when the league average was .262) with a .712 OPS. He collected 2,041 hits despite the short schedules of the day (8th all-time at the time of his retirement).

Glasscock ranks 12th all-time among eligible shortstops in WAR batting runs (ahead of 11 Hall of Famers). He really stands out defensively, ranking 6th all-time in fielding runs (behind only three Hall of Famers—Ozzie Smith, Cal Ripken Jr., and Joe Tinker). Ripken is the only player ahead of him on both lists.

Peer Comparison

From 1871–1900, 24 players had 2,000 or more plate appearances and played shortstop in over half their games. Glasscock ranks very well among them:

- 1st in games

- 2nd in plate appearances (behind Ed McKean)

- 3rd in runs (behind Herman Long and McKean)

- 2nd in hits (behind McKean)

- 1st in doubles

- 4th in triples (behind McKean, Dahlen, and Tommy Corcoran)

- Tied for 7th in home runs

- 3rd in runs batted in (behind McKean and Long)

- 2nd in stolen bases (behind Long)

- 6th in batting average (but 2nd among players with 5,000+ plate appearances, behind only McKean)

- 7th in on-base percentage (but 3rd among players with 5,000+ plate appearances, behind McKean and Long)

- 10th in slugging percentage (but 3rd among players with 5,000+ plate appearances, behind McKean and Long)

- 7th in OPS+ (but 3rd among players with 5,000+ plate appearances, behind only Dahlen and McKean)

- 2nd in WAR Batting Runs (behind Hughie Jennings)

- 2nd in WAR Fielding Runs (behind Germany Smith)

Let’s run down his competition:

- Ed McKean appears quite often. McKean could hit, collecting a 114 OPS+ and 150 batting runs in 1,655 games. But he was a dreadful defender, considered the worst of the 19th century according to historians and advanced metrics. As a result, his Hall Rating is just 69.

- Herman Long played a long time and compiled 2,129 hits. But he was a below average hitter (94 OPS+ and -82 batting runs) and not quite the defender Glasscock was. His Hall Rating is just 58.

- Tommy Corcoran and Germany Smith were great defenders, but they couldn’t hit at all. Their Hall Ratings are 23 and 35, respectively.

- Hughie Jennings, of course, is already in the Hall of Fame. He basically got in through an incredible 5-year peak, as his Hall Rating is just 87. He also won three pennants as manager of the Detroit Tigers, so that likely helped his case.

One shortstop who didn’t appear in these rankings was John Ward (93 Hall Rating). Ward split time as a pitcher and shortstop, so he had something of an odd career. In 1890, W.I. Harris of the Wheeling Register compared Glasscock to his peers and the name that appeared most often was Ward’s:

There are only two short stops who can approach Glasscock in fielding. These are Ward and Williamson; only one who can equal him in brilliant plays-Ward; none that can excel him in batting, and only one-Ward again-who can equal him in base running.

Ward was a great fielder, though he doesn’t rate as highly as Glasscock (by advanced or traditional metrics). Ward was a below-average hitter, but he certainly could pitch (before ruining his arm) and was a great baserunner.

Ed Williamson rates as an excellent fielder, but he only played four seasons at short (the rest at third). Those happen to be his worst defensive years (by WAR’s fielding runs). He could hit about as well as Glasscock, but not nearly as long (he managed just 1,159 hits).

Traditional Defense

The comparisons above show that quite a bit of Glasscock’s value came from his defense. That holds true for plenty of Hall of Fame shortstops, but can we really trust these advanced metrics for 19th century players?

Glasscock, like Dahlen, was considered one of the top fielders of his time (if not the best). But if you’re skeptical of advanced defensive metrics and more into traditional ones, take a look at these:

- Fielding Percentage at SS: 12 times in Top 3, 6 times led league (and a second place finish in his only season at 2B)

- Assists at SS: 8 times in Top 3, 6 times led league

- Putouts at SS: 9 times in Top 3, 2 times led league

- Range Factor per Game at SS: 9 times in Top 3, 3 times led league

No matter which lens you use—traditional, sabermetric, or anecdotal—Glasscock was an elite defender. His excellent bat and longevity make him a very worthy Hall of Famer. The key issue is that strong defense, a strong bat, and longevity at an incredibly valuable position doesn’t always translate into induction. In addition to Glasscock, both Bill Dahlen and Alan Trammell fit that profile without induction. Hall Rating believes that Dahlen, Trammell, and Glasscock are three of the most egregious Hall of Fame snubs out there.

What’s Next?

Due to the changes to the Hall of Fame’s Era Committees, the earliest Glasscock will ever appear on an Early Baseball Era ballot is 2020 (for 2021 induction). Given that he didn’t appear on the Pre-Integration Era ballot in either 2013 or 2016, he’s far from a lock to even be nominated. But rest assured, I’ll be banging the drum.

Some may wonder what the point of all of this is. After all, Glasscock died in 1947. The point is that if a player was worthy of the Hall of Fame, he should be a Hall of Famer—whether he retired five years ago or 125 years ago.

Last Updated: July 29, 2016