Rick Reuschel, Baseball-Reference’s Pitching WAR, and Hall of Fame Value

Mar 1, 2021 by Adam Darowski

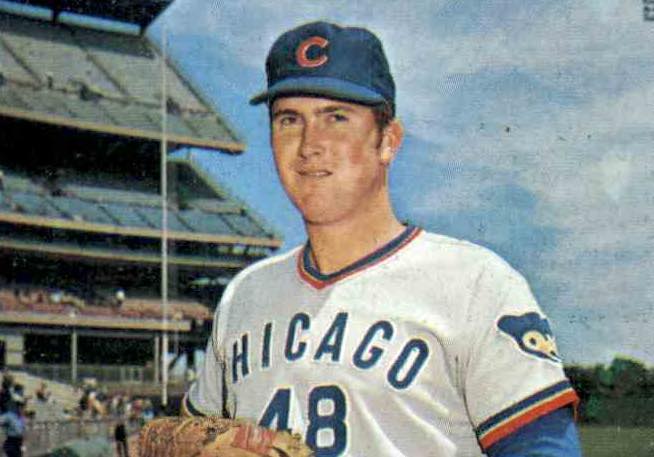

I was recently on the 1988 Topps Podcast to talk about Rick Reuschel. While preparing for the podcast, I collected my thoughts into this article. I’ve included the episode below. This podcast is straight up one of my favorites. I can’t recommend it enough.

Who is the best eligible pitcher outside the Baseball Hall of Fame? It’s an easy question with just one possible answer—Roger Clemens. Who’s next? Most would probably say Curt Schilling.

But those two are a little complicated. Who is the best eligible pitcher outside of the Baseball Hall of Fame… besides them? This question becomes much more difficult to answer.

When trying to answer this type of question, WAR (Wins Above Replacement) is a great place to start. Even though I run an alternate Hall of Fame populated by a mathematical formula, I don’t actually believe that the Hall of Fame induction process should simply be replaced by a descending sort of a single stat. But WAR offers us an excellent conversation starter.

These are the top eligible pitchers outside of the Hall by WAR:

- Roger Clemens (138.7)

- Curt Schilling (80.5)

- Jim McCormick (76.0)

- Kevin Brown (68.2)

- Rick Reuschel (68.1)

- Luis Tiant (65.6)

- Bobby Mathews (62.3)

- Tommy John (62.1)

- David Cone (61.6)

- Tony Mullane (61.1)

As much as I love nineteenth century baseball, this list is dominated a bit too much by early workloads (with McCormick third, Mathews seventh, Mullane tenth, and Tommy Bond just behind Mullane). Hall Rating (from the Hall of Stats) combines pitching and hitting WAR and Wins Above Average (WAA) while making several adjustments—one of them for the workloads of nineteenth century hurlers.

These are the top eligible pitchers outside of the Hall by Hall Rating:

- Roger Clemens (288)

- Curt Schilling (170)

- Kevin Brown (135)

- Rick Reuschel (134)

- Luis Tiant (127)

- David Cone (127)

- Bret Saberhagen (120)

- Dave Stieb (112)

- Kevin Appier (110)

- Tony Mullane (110)

A Hall Rating of 100 represents the Hall of Fame borderline (not the average, which is used by JAWS). It’s also worth noting that this list does not include pitchers from the Negro Leagues. While the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database includes WAR and WAA, these stats have not yet been merged with the official record. No pitcher in the Negro Leagues database has a higher WAR total than Satchel Paige’s 50.8, but these stats are not based on 162 game seasons. Hall Rating includes an adjustment for shorter seasons, so it’s quite likely we’ll see Negro League pitchers like Dick Redding eventually join this list.

Back to our original question—who’s the best eligible pitcher outside the Hall? Of course, Roger Clemens would be in the Hall of Fame if not for ties to performance-enhancing drugs. Curt Schilling would be in already if he didn’t… [gestures at everything]. Kevin Brown (near the top of both lists) was named in the Mitchell Report, which likely contributed to his one-and-done Hall of Fame candidacy.

Who’s next? Is it McCormick, a relatively unknown 19th century pitcher who has gained prominence thanks to WAR? Maybe Tiant, who was capable of 21 wins and a 1.60 ERA one season and 20 losses and a 3.71 ERA (literally) the next? What about Cone, who failed to win 200 games but struck out a lot of batters and won a strike-shortened Cy Young? Are we simply not impressed with these lists and need to dig deeper to find a high-peak, short-career star like Johan Santana (who was one-and-done as recently as 2018)? Is it a low-peak, long-career guy like Tommy John or Jim Kaat? How about a reliever like Billy Wagner?

Or do we finally pay attention to the fact that Rick Reuschel is sitting right there in front of us, near the top of both lists.

Rick Reuschel pitched for 19 seasons in the Major Leagues for the Cubs, Yankees (briefly), Pirates, and Giants. He won 214 games and lost 191 (.528 winning percentage) with a 3.37 ERA (114 ERA+) and 2015 strikeouts against 935 walks in 3548⅓ innings pitched. Bill James’ similarity scores compare Reuschel with Jim Perry (215–174, 3.45 ERA, 106 ERA+, 38.4 WAR), Jerry Reuss (220-191, 3.64 ERA, 100 ERA+, 32.9 WAR), and Claude Osteen (196-195, 3.30 ERA, 104 ERA+ 36.8 WAR). None of these pitchers is remotely close to the Hall of Fame. Yet Rick Reuschel has a staggering 68.1 WAR according to Baseball-Reference. What gives?

I first wrote about Reuschel’s Hall of Fame case back in 2013 for High Heat Stats. In that article, I noted that you don’t have to dig too deeply to start noticing that Reuschel was probably better than you remember:

Reuschel’s raw numbers are actually nearly Hall-worthy. He had a .528 winning percentage and 114 ERA+. Nolan Ryan had a .526 winning percentage and an ERA+ of 112 (I understand Ryan pitched longer, but still… this is a little surprising).

Just 35 eligible pitchers in history have had a better ERA+ than Reuschel in more innings. 30 are in the Hall of Fame. The ones who are not are Clemens, three nineteenth century pitchers (McCormick, Mullane, and Bond), and Jack Quinn (who had his best season in the Federal League and pitched past age 50).

Over the course of his career Reuschel’s teams managed a .473 winning percentage, which dragged down his winning percentage. His teams were also dreadful in the field, which hurt his ERA (and ERA+). ERA excludes earned runs, but unearned runs only happen as a result of errors. A player can only make an error on a ball that he actually reaches. Lack of range from the defense is not reflected in a pitcher’s ERA (or ERA+). Just about every statistic that came before WAR under-rates Rick Reuschel.

Let’s take a deep dive into why WAR likes Reuschel so much.

First, it’s important to note that there are two distinct flavors of pitching WAR. One is published by Fangraphs and is based on fielding independent pitching (FIP). Fangraphs WAR aims to take the pitcher’s defense out of the equation by focusing only on the things the pitcher can fully control—walks, strikeouts, and home runs. Baseball-Reference takes a different approach. It starts with the total runs allowed by the pitcher and then makes adjustments for park, defense, opposition, and more.

Sometimes a pitcher can look good through one WAR lens but not the other. Jack Morris was worth 55.8 WAR according to Fangraphs (fWAR), but just 43.6 WAR on Baseball-Reference (bWAR). Meanwhile, McCormick totaled 76.0 bWAR but just 40.0 fWAR. Reuschel, however, excels in both. He’s worth 68.1 bWAR and 68.2 fWAR.

To calculate Rick Reuchel’s bWAR, we compare his runs allowed per nine innings to the number of runs per nine innings an average pitcher would be expected to surrender when pitching in the same context as Reuschel. What do we mean by “pitching in the same context as Reuschel?” This includes:

- Facing the same opponents Reuschel faced

- In front of the same defense Reuschel played with

- In the same parks Resuchel played in

- In the same role as Reuschel

- In situations with the same leverage as Reuschel

We start with the average number of runs scored by the opponents Reuschel faced, which is 4.14 runs per nine innings. Reuschel allowed 3.79 runs per nine innings (this includes earned runs and unearned runs), so we can already see that Reuschel was considerably above average. The 4.14 does not take into account the context in which Reuschel pitched. It turns out we need to make some pretty large adjustments—the biggest for the defenses Reuschel played in front of.

The quality of the defense behind Reuschel is measured through Rfield, bWAR’s fielding component, which is based on Total Zone Rating (TZ) or Defensive Runs Saved (DRS) since 2003. A value of zero means the pitcher’s defense performed at an average level. A positive value means the defense saved the pitcher runs (and that credit is taken from the pitcher and given to the fielders). A negative value means the defense cost the pitcher runs (and that credit is taken from the fielders and given back to the pitcher).

Reuschel’s defense cost him 0.18 runs per nine innings. When we extrapolate that over 3548⅓ innings it adds up to nearly seventy runs. Since 1900, these are the pitchers hurt the most by their defenses (with the number of runs their defenses cost them):

- Phil Niekro (-109)

- Tom Candiotti (-77)

- Larry Dierker (-77)

- Ned Garver (-71)

- Wilbur Wood (-70)

- Rick Reuschel (-70)

- Turk Farrell (-68)

- Pedro Ramos (-66)

- Kenny Rogers (-61)

- Kevin Gross (-60)

Playing in front of weak defenses for so long requires a pitcher to get a lot of extra outs. bWAR gives Reuschel credit for this. On the opposite end of the spectrum we have Jim Palmer. No pitcher in history was helped more by his defense. Palmer’s defenses saved 143 runs more than the average defense. That is a huge advantage that is not captured in ERA and ERA+, but is captured in WAR. If you put Palmer’s defense behind Reuschel, you’re looking at a swing of 213 runs (more than 20 wins) over the course of his career. That’s enormous.

Does this pass the eye test? Reuschel didn’t play with a Gold Glove defender until he was 34 years old. By that time, Jim Palmer had played with 34 Gold Glove winners (ten by Brooks Robinson, nine by Mark Belanger, seven by Paul Blair, four by Bobby Grich, three by Davey Johnson, and one by Luis Aparicio)—not counting four won by Palmer himself. Eddie Murray would add three more before Palmer retired.

While the defensive adjustment is certainly the largest one that helps Reuschel’s case, it is not the only one. There are also park factors to consider. A park factor of 100 means the park had no explicit advantage to hitters or pitchers. Over 100 favors hitters and under 100 favors pitchers. Sandy Koufax provides a good example of park factors. In Koufax’s three seasons in Brooklyn, Ebbets Field favored hitters (105.7). During Koufax’s first four seasons in Los Angeles, the Dodgers played in the LA Coliseum—also a hitters park (104.9). Then they moved to Dodger Stadium where Koufax ripped apart the National League (but was helped by a 92.4 park factor).

Reuschel had a 104.6 park factor for his career, playing in a hitters park for the bulk of his career in Chicago, finishing in a pitcher’s park in San Francisco, and stopping at more neutral parks in New York and Pittsburgh in between.

The next adjustment that WAR makes is for a pitcher’s role. Starting pitchers generally allow more runs than relief pitchers because they need to pitch longer, not in short bursts. Reuschel started the vast majority of his games, so he is given an adjustment of 0.13 runs per nine innings, or about 51 runs over the course of his career. Compare that to Mariano Rivera, who was almost exclusively used in relief. Rivera’s adjustment is -0.35 per 9 innings, or about -50 runs for his career.

The last adjustment isn’t a major one for Reuschel as it has to do with the leverage of his relief situations. If we go back to the 4.14 runs per nine innings scored by the opponents Reuschel faced, some of those innings were pitched by relievers in high leverage situations. Since Reuschel didn’t pitch in high leverage relief situations, 1.6 wins are subtracted from his Wins Above Average (WAA). This same adjustment credits Rivera with 10.1 additional wins because so many of his innings were in high leverage situations.

For Reuschel, the worst part is that his defense and ballpark adjustments were at their most detrimental during his peak (his first decade with the Cubs). While he was pitching at his best (about 50 WAR in ten seasons), his numbers were being defaced by a lousy team (.464 winning percentage) with a lousy defense (costing him an additional 0.34 runs per nine innings), in a hitter’s park (107.6 park factor).

While the average pitcher we’re comparing Reuschel to initially allowed 4.14 runs per nine innings, that rises to 4.65 runs per nine innings after adjusting for the context of Reuschel’s career. Suddenly Reuschel’s 3.79 runs per nine innings goes from looking well above average to excellent.

The difference between these two figures translates to 68.1 pitching WAR—34th all time and fifth among eligible pitchers outside of Cooperstown. Since there are 73 pitchers in the Hall of Fame for their Major League careers, ranking 34th all time should really get Reuschel more consideration for Cooperstown. Hopefully this stroll through the inner workings of Baseball-Reference’s pitching WAR shows that this isn’t just a made up number—it’s the result of surprisingly solid traditional stats combined with several contextual adjustments. I feel comfortable proclaiming that Rick Reuschel provided Hall of Fame value over the course of his career.

If a player provided Hall of Fame value, does that automatically make him a Hall of Fame player? I don’t think there’s a single player in Major League history who illustrates the difference between these two phrases more than Rick Reuschel. He appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot in 1997 and received just two votes (0.4%). His list of accomplishments is rather modest:

- Never won a championship (pitched in two World Series)

- Won his first postseason game at age 40

- 3-time All Star (two after age 38)

- 2-time Gold Glove (both after age 36)

- Two Top-3 Cy Young finishes (and one more 8th place finish)

- 1985 Comeback Player of the Year

Yes, it’s the Hall of Fame and not the Hall of Stats. But when the stats are this good, it’s really not the player’s fault he wasn’t famous. Reuschel was already overlooked during his career relative to the value he produced. Using that to overlook him again feels wrong.

If a player’s stats are on the borderline, “fame” (however you want to measure it) can be an appropriate deciding factor. Reuschel’s value, however, was not borderline. He ranks solidly in the top half of Hall of Fame pitchers. From a value standpoint, Rick Reuschel would raise the quality of the Hall of Fame. Personally, I think that’s a Hall of Famer.